Story and drone photos by Rob Levine | January 11, 2025

In 2021 the Minnesota Supreme Court had overturned the overarching Permit to Mine for the PolyMet project and ordered a so-called "contested case hearing" to dig into the company's planned method of reclaiming its hazardous tailings. Two and a half years later Administrative Law Judge (ALJ) James E. LaFave affirmed the Supreme Court's decision to deny the permit.

At that point the project was in effect a "Dead Mine Walking," as three of its major permits had been overturned. The only question was if the DNR, whose work on the project had been suspect from the beginning, would pull the plug, or whether it would find some way to avoid a negative precedent.

According to Minnesota law, decisions made by administrative law judges in contested case hearings are merely recommendations made to the commissioner of the agency that has called the hearing, and parties to the hearing are free to make arguments to the agency after the judgment, until a so-called closing of the record. After that the agency has 90 days to act on the administrative law judge's decision, or it is automatically accepted.

Back in February 2022 the DNR had announced it had appointed Grant Wilson, at the time one of the agency's regional directors, as the 'decider' on what the agency would do with the ALJ's eventual recommendations. This was necessary because the DNR's commissioner and her General Counsel are both involved in the case.

The DNR was now split in two. Wilson would represent the DNR as an institution. And the so-called DNR "Hearing Team" would defend the Permit to Mine. No one in the DNR would defend the environment.

Debate about the decision then began in earnest between two environmental nonprofits, WaterLegacy and the Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy, and the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa (the Band) on one side, versus the mine's new owner, NewRange, and the rump Hearing Team supposedly walled off from the DNR's actual decision-making process on the other.

During the contested case hearing process ownership of the mine actually changed hands as two foreign mining giants each took an equal stake in a new entity, NewRange Copper Nickel, based in Babbitt, Minnesota. The environmental groups and the Band each filed challenges to this with the DNR, but the agency held firm even though the name of the legal owner of the proposed mine isn't even on the Permit to Mine.

PolyMet is no more - it is now 100% owned by Glencore.

Then in February 2024 NewRange figuratively blew up the process when it sent an email to the Band informing them it was reevaluating the project, especially the so-called "Flotation Tailings Basin" - the waste storage site that is the center of controversy and the subject of the administrative law judge's ruling against the project.

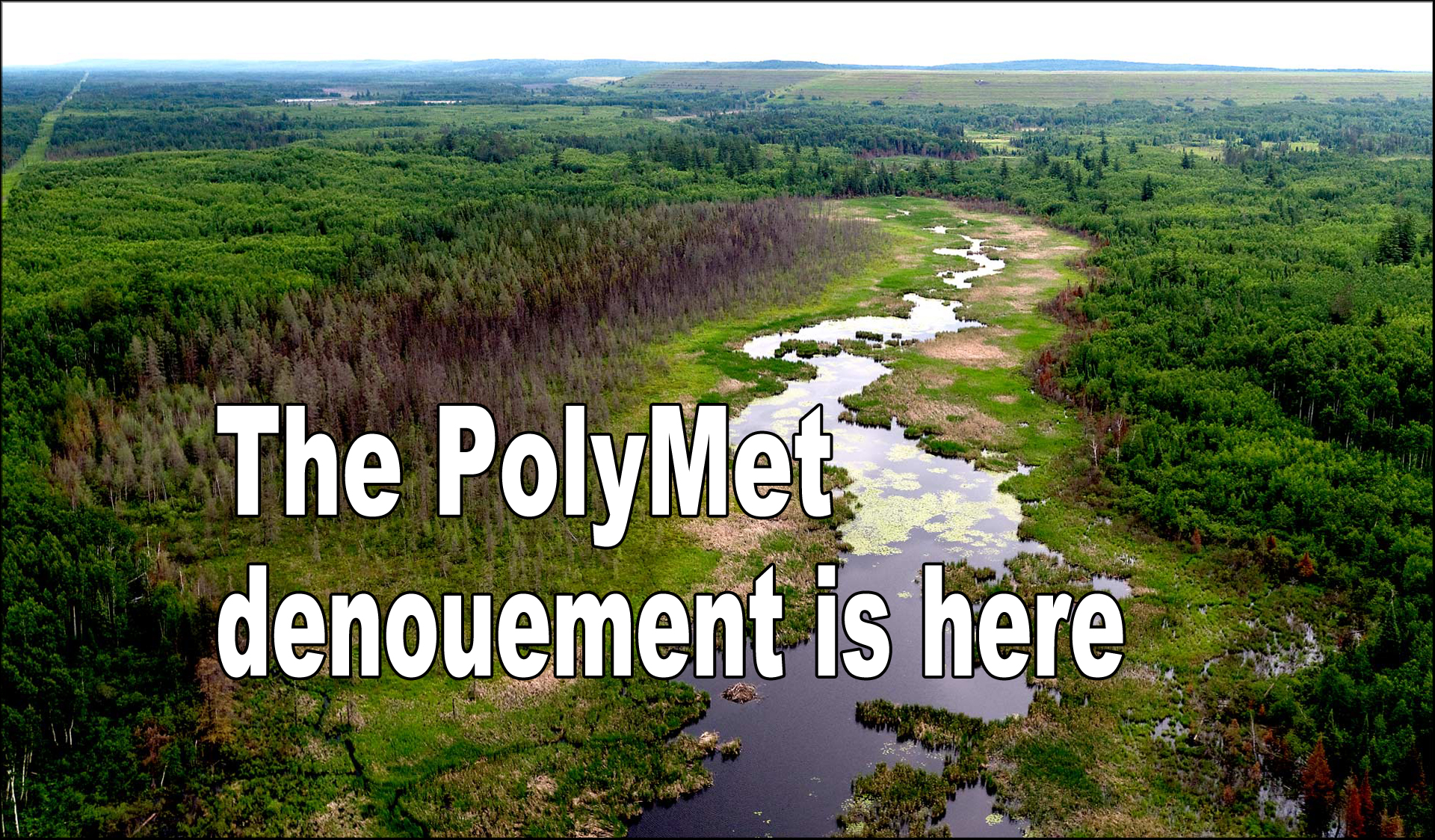

Google Earth image of the PolyMet Flotation Tailings Basin (FTB) (2023 image)

The Band in turn urged the DNR to declare the entire process moot in a March 11 communication to Grant Wilson (the decider) because, they claimed, PolyMet had now said it was abandoning the Flotation Tailings Basin.

That communication, along with a Duluth News Tribune story on the email the following month, defined the legal back and forth until May, when Wilson ruled that he wouldn't stay or moot the proceedings, and that the parties should get on with their real arguments over the ALJ's decision.

It's worth noting that when Wilson eventually did issue his nine month stay of the proceedings in November he cited this exact issue - NewRange's documented intent to back away from the project as permitted. In the first case Wilson ignored the fact that everyone knew that the mining company's intent had changed, all the while insisting that he did have the right to issue a stay. In the second case, in November, Wilson based his decision on a press release issued by the company in August.

Nevertheless Wilson's decision to plow forward with the process last May has probably unintentionally given us one final look into the sophistry and gaslighting that has been the hallmark of both the DNR and NewRange's arguments throughout this entire 15 year journey.

The alchemists of the Minnesota DNR

Today three major permits for the proposed NorthMet project are either overturned or suspended. The National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System [water pollution] permit issued by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency in December 2018 was overturned by the Minnesota Supreme Court in August 2023. The wetlands destruction permit issued by the Army Corp of Engineers in March 2019, needed to bulldoze the wetlands over the proposed open pit mine, was suspended by the Corp of Engineers itself in the March 2021.

Then there's the Permit to Mine. The parties to the contested case hearing have been fighting over many aspects of the proposed mine for a long time, from well before the actual permit was issued in late 2018. The issue at hand is how the tailings, a toxic mix of heavy metals, neurotoxins and acid precursors the consistency of sand or finer, will be dealt with after the mine's closure, projected to be about 20 years after it opens.

State law classifies these tailings as "Reactive Mine Waste," and specifies how they must be dealt with. Miners are given a choice: either somehow modify the waste so it is no longer reactive, or store it in such a way that prevents "substantially all" water from interacting with it, forever, without mechanical or other ongoing interventions.

PolyMet's plan to meet this rule has been to use a clay mixture featuring the active ingredient in cat litter to somehow prevent the reactive mine waste inside a modified existing iron mining tailings basin from forever contacting water.

The legal questions defining the contested case hearing were about that plan. Would the clay mixture forever prevent "substantially all" water from traversing the stored tailings?

Judge LaFave had answered that question in the negative in November 2023, citing admissions from the defendants that 300 million gallons of water a year would traverse the tailings and need to be captured at the bottom and pumped back to the top. LaFave put it bluntly that "Petitioners maintain that whatever the term [preventing] 'substantially all' means, that is not it."

In their responses to Judge LaFave's recommendations both the Hearing Team and NewRange then made suspect claims that the proposed waste storage system satisfies both of the Reactive Mine Waste rule's options, and as such Wilson should throw out his determinations.

How would NorthMet satisfy the first part of the Reactive Mine Waste rule, that requires the owners to

"...modify the physical or chemical characteristics of the mine waste, or store it in an environment, such that the waste is no longer reactive."

DNR lawyers turned this simple phrase on its head by picking and choosing words from various parts of the law to come to the conclusion [page 16] that reactive mine waste somehow becomes not reactive even as water continuously flows over it creating a toxic soup, so long as the miners can claim that none will escape to the surrounding groundwater:

"Taking all of these terms together, mine waste remains reactive if substances flow out from the waste, beyond the environment in which it is stored, and cause impacts to natural resources that the commissioner determines are unacceptable. Conversely, the rule is satisfied if mine waste is stored in an environment such that substances do not flow out from the storage environment and cause impacts to natural resources that the commissioner determines are unacceptable." [emphasis added]"

This bizarre interpretation that waste isn't reactive unless it escapes the storage environment is contradicted both by the existing Reactive Mine Waste rule and the contemporaneous history of the creation of the rule in 1992.

Reactive Mine Waste is defined in state administrative rules, which carry the weight of law, as waste that "...is shown through characterization studies to release substances that adversely impact natural resources." [emphasis added]

We also know from the Statement of Need and Reasonableness (SONAR) filed with the creation of the rule that

"To meet the first requirement, measures would have to be taken to prevent substances, that adversely impact natural resources, from forming within the mine waste. " [emphasis added]

So the DNR and NewRange argued that waste is not reactive unless it escapes from storage, while the documentation from the creation of the rule says the option's purpose was to stop harmful substances "from forming within the mine waste" - something that would happen continuously within the PolyMet tailings basin for at least hundreds of years.

The argument also relies upon the DNR and NewRange's dubious assertions that no pollution will escape from the tailings basin into the surrounding groundwater. Both claim a so-called "no-flow boundary" will be established around the tailings basin; but earlier figures on seepage capture rates were considerably less confident, predicting up to 10% of the waste could escape, while in other contexts expert geologists have questioned the accuracy of containment predictions.

Then there's the claim to have met the second part of the Reactive Mine Waste rule as well, the part that requires at closure that "substantially all" water is prevented from interacting with the tailings.

The SONAR document from the rule's creation specifies that the first option is preferable, because, as the document says, " If no such substances are allowed to form, it can reasonably be expected that no impact will occur."

In turn the key phrase in the second option requires that miners "...permanently prevent substantially all water from moving through or over the mine waste..." [emphasis added]

The issue being fought over since the environmental groups and the Band first sued in the appellate court was whether PolyMet's planned low-cost solution for covering the tailings in the basin would actually satisfy the Reactive Mine Waste rule, and prevent "substantially all" water from contacting the tailings, forever. Judge LaFave agreed with the Supreme Court and said it wouldn't.

Both the DNR and NewRange then argued in their communications that LaFave erred in judging the law by the absolute amount of water that would traverse the tailings, and not by the percentage of possible water that could potentially interact with them.

This is a strange argument for the DNR to make, because besides promoting mining it has an equal mandate to protect the state's natural resources, and if this particular position was adopted it would mean that the more reactive mine waste a company generated the more it would be allowed to create dangerous substances with the potential to harm the environment.

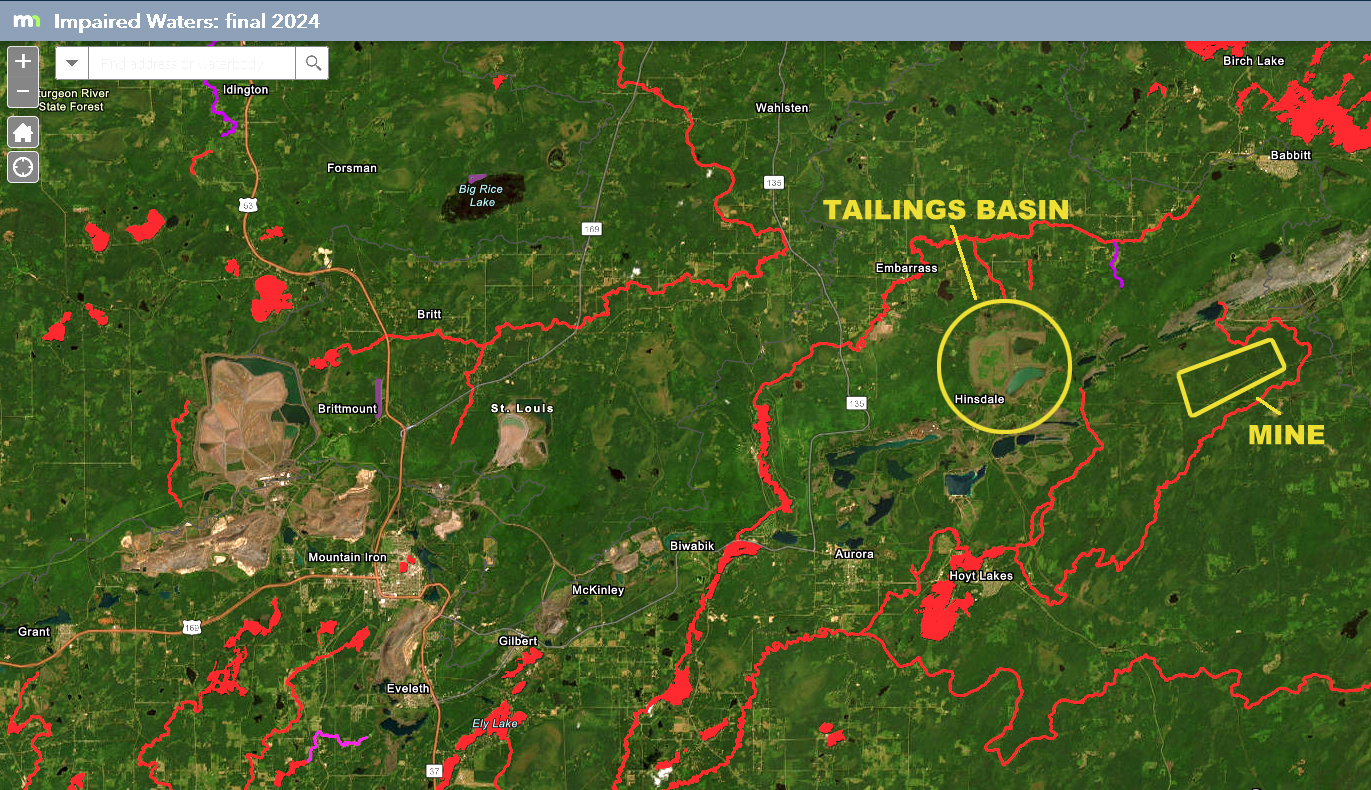

And it's not like the waters surrounding the planned mine and processing plant are doing so well right now. According to the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency's most recent survey, nearly all the waters in the area are already impaired:

Nearly all the waters surrounding the NorthMet project are already impaired according to the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency's latest survey

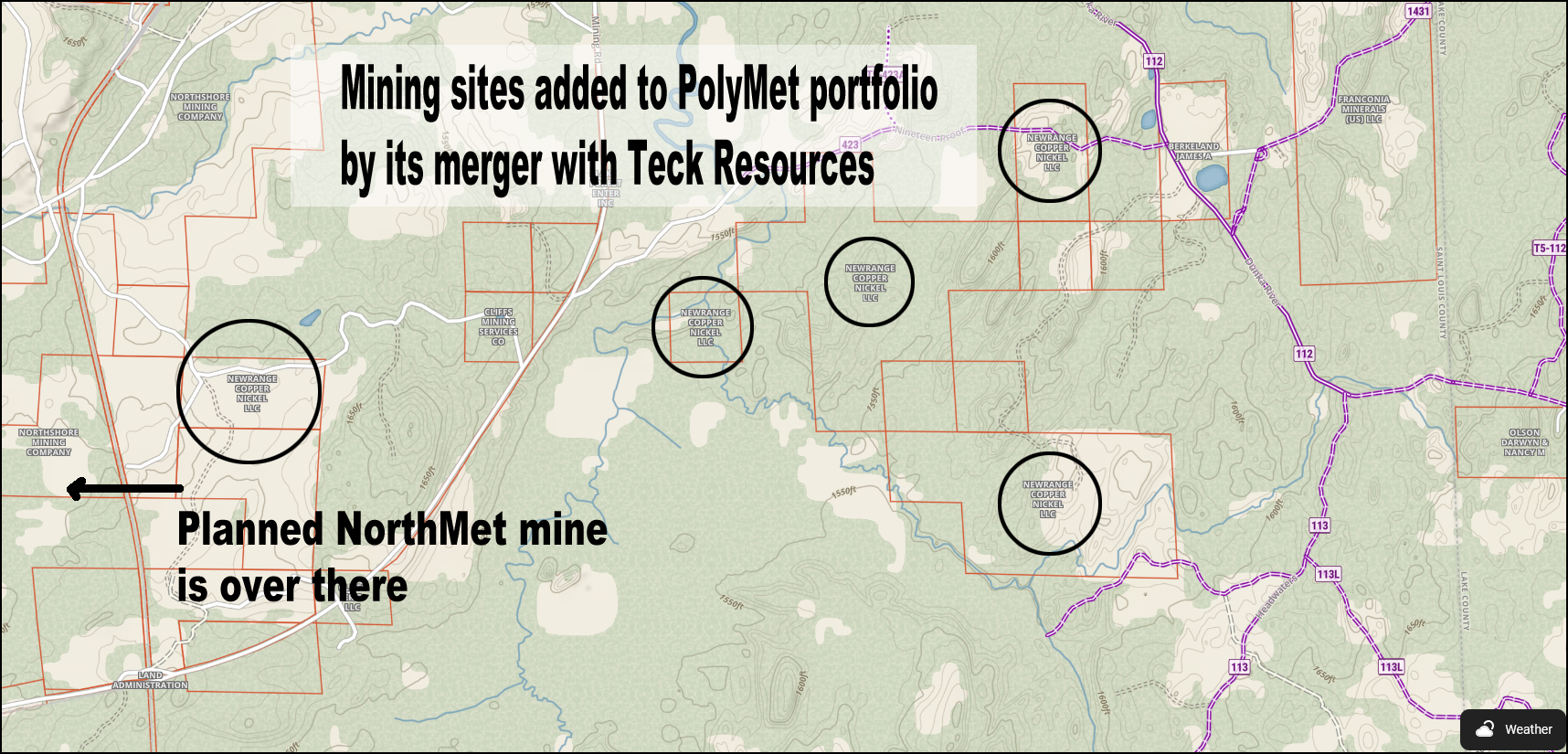

For now, and for the foreseeable future, the NorthMet project is dormant, if not dead. But in all likelihood it will be back, even bigger and more dangerous. The change in ownership in 2023 brought in Teck Resources of Canada, which owns similar copper nickel deposits just east of the planned NorthMet mine. Given the low grade of the NorthMet deposit, this additional ore could potentially make mining in this environmentally sensitive area more economically plausible.

When PolyMet dissolved itself into an equal partnership between Teck Resources of Canada and Glencore of Switzerland it picked up an array of new potential sulfide mine sites

Other mining companies appear to have gained some insight from PolyMet's losses. The proposed Talon sulfide mine, under the city of Tamarack, about 50 miles due west of Duluth, claims it will obviate the tailings question by shipping raw ore to North Dakota for processing.

The proposed Talon sulfide mine under the city of Tamarack claims it will obviate the tailings problem that has crippled NorthMet by shipping its ore to North Dakota for processing.

Yet it remains to be seen whether the DNR itself has learned anything from the PolyMet saga. For 15 years the agency has been cutting corners, doing shoddy geological, engineering and legal work, all in the service of helping foreign companies mine low grade ore on the cheap in one of the most environmentally sensitive areas in the state. Its preposterous legal arguments made in June, signed by the agency's General Counsel and paid for with over $2 million to the outside law firm Holland & Hart,** show that nothing has changed.

Throughout the process mining advocates have argued that PolyMet has followed all the laws and regulations, and that proved the project was safe. Only, those sulfide laws and regulations, slim as they are, have never been tested. And it turns out PolyMet and the DNR weren't following those laws and regulations after all, and it took courts to wriggle out those facts.

So it's fair to say that without the work of WaterLegacy, Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy, and the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, NorthMet would already be up and running, spilling millions of gallons of toxic waste into the already impaired waters between Babbitt and Hoyt Lakes. Until we can un-capture the DNR we'll be relying on those organizations to protect one of the most unique and important areas of the state.

* Courts still call the project PolyMet even though the legal owner is now NewRange Copper Nickel, and the project itself is called NorthMet

**The invoices are redacted, but a few show payment for other projects, including about $11,000 for work on Mesabi Metallics

-- 30 --